Welcome to the second part of my history of StarWarp Concepts, which is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year.

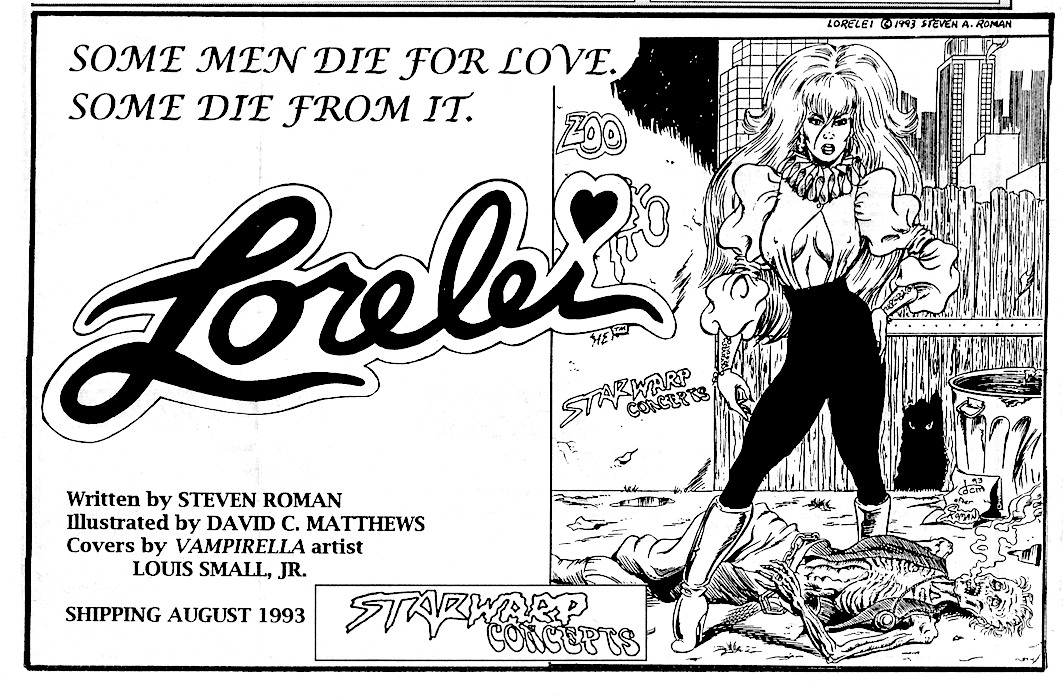

In Part 1, we left off in 1992. After breaking ground by publishing a few digest-size comics between ’89 and ’92, I decided the time had come to move up to full-size comics, and that Lorelei would be the title to help launch the new SWC as an indie publisher. But unlike the small-press version, I wouldn’t be drawing it, just writing it. I’m an incredibly slow artist, so there was no way I’d be able to keep a series on schedule.

So I put out some feelers to see if I could interest someone in tackling the art chores. That someone turned out to be David C. Matthews, another small presser who’d been writing, drawing, and publishing his own comic: Satin Steele, about the adventures of a female bodybuilder. I approached Dave with the notion of teaming up and thankfully he was all for it. And after he completed some try-out sketches, the change in artists was settled, and much for the better; now the series needed a direction.

My decision was that we’d start out by telling a detailed origin story for Lorelei: about 14 issues’ worth! And that Lorelei—the flame-haired seductress who’d appear on every cover in order to attract potential buyers—wouldn’t appear until late in the story. Rather, this would be the tale of Laurel Ashley O’Hara, a controversial, social-issues-driven photographer whose work was lauded and hated by critics—and who was the woman fated to become Lorelei.

But not yet. Not for a while. Not until she’d been drawn into the terrifying plans of a mystery man named Lord Arioch, whose plans for Laurel involved using her as a new receptacle for the soul of his dying wife…who was a demonic succubus.

Fourteen issues’ worth of plans.

In retrospect, it was a knuckleheaded idea taking far too much inspiration from writer/artist Dave Sims’s seminal work, Cerebus, in which his decompressed storylines sometimes ran as long as 25–30 issues and were later republished in phonebook-sized volumes (these days, the popular term is “omnibuses”). For some reason, I thought that was a fantastic approach that would elevate Lorelei above the level of the “bad girl” comics—Catwoman, Vampirella, Lady Death, and the like—that were just beginning to sprout up on comic shop shelves.

Like I said: knuckleheaded. For one thing, those mainstream titles were full color; Lorelei would be black and white. All the successful comic book bad girls wore either skintight spandex or lingerie and stripper heels; Lorelei was almost fully clothed, except that the big, flouncy blouse she wore was unbuttoned to expose her cleavage (she’s a succubus, remember). Their adventures were straight-up T&A (think boobs and butts) comics; Lori’s origin would be taking more of an art-house-movie approach, focusing on characterization over titillation (another influence on me: the films of writer/director John Sayles, of The Brother from Another Planet and Eight Men Out fame).

Dave Matthews wasn’t too fond of the approach—he’d signed on to draw the sexy chick who kills bad guys with her kiss, and not just on the covers. I told him it would all work out. Hopefully.

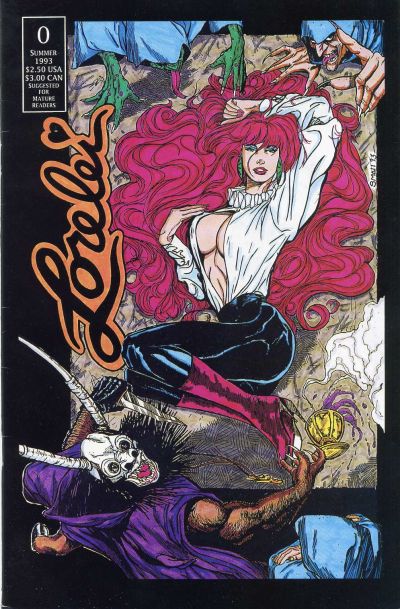

And it did, in a way. Lorelei #0 sold a little over 2,500 copies. Lorelei #1 did even better, racking up sales of over 5,000 copies! Not bad at all for a black-and-white comic from a small indie house…whose bad-girl lead didn’t even appear inside the issues.

What helped a great deal was that both covers had been drawn by Louis Small Jr., an artist who was being lauded for his work as the penciller of Harris Comics’ then-recent relaunch of Vampirella, the former Warren Publishing outer-space bloodsucker whose series ended in 1982. Vampi was now leading the charge into what became known as “The Bad Girl Era,” that decade-long period of the 1990s when every publisher was putting out comics starring half-naked superheroines and vampires.

(How did a small-time publisher like me get covers out of a superstar artist? Oddly enough, for all the praise Louis was getting in comics circles, Harris was doing nothing to promote him. When we met at a comic con in early 1993, Harris had Louis at their booth, but all the art they had on display was by the artist who was following Louis on the series—and Louis was pissed. So, when a fellow small presser named Christopher Paris was talking to Louis at the show and saw me walking by, he called me over and said to Louis, “This is the guy I was just telling you about—the big fan of your Vampirella work!” My outpouring of respect—more than Harris Comics was showing him—led to Louis, right on the spot, offering his cover services for free.)

With Lorelei #2, however, sales dropped back to around 2,500 copies. Not an unexpected event—even then, it was pretty common knowledge that the second issue of a series always loses half the retailer orders of a #1 (even though in our case this was the third issue of Lorelei).

But then they remained at that level, around 2,500 copies, through issue 5. Respectable numbers, but eventually production costs outweighed the marginal profits and I had to cancel the series—it just wasn’t generating enough income. The 60% discount given to distributors was and remains a killer to small publishers—on a $2.50 comic like Lorelei, that meant they were getting $1.50 off cover price. Not to mention what I was paying for printing and shipping. Bottom line? I wasn’t making any money. The company wasn’t making any money. Worst of all, I wasn’t able to pay Dave Matthews for his work on the last couple of issues.

It wasn’t too bad an effort for a black-and-white indie comic in the 1990s, even with the decompressed storytelling. It just wasn’t enough.

In the middle of all that, the comics distribution market utterly collapsed. It started with Marvel foolishly and stubbornly deciding that they were more than capable of handling the distribution of their own product to retailers—even though they’d never done it before. According to one store owner I’d talked to around that time, one reason for this approach was that Marvel’s sales department had, at an industry sales conference, apparently let it slip that they had a real problem with retailers selling back issues for higher than cover price. Why a problem? Because Marvel wasn’t getting any of that money from the markups; it all belonged to the retailers. There had to be some way around that…

So at the end of 1994, the House of Ideas went out and bought one of the comic distributors, Heroes World, and then canceled their accounts with everybody else—and Marvel was one of the major publishers whose wares were keeping the other distributors in business. But now, if you wanted a Marvel title in your store, you had to go through them and nobody else. According to Chuck Rozanski, owner of comic shop Mile High Comics, that move caused distributor sales to drop by 35–40%.

Then the other major players—DC, Dark Horse, and Image—signed exclusive deals with the largest company, Diamond Comic Distribution, which now meant all the other distributors were cut off from their main sources of income. It left them with the smaller indie publishers, and none of us were generating the kind of sales that would help keep them afloat.

When the dust settled, only one distributor was left standing: Diamond. Everyone else had been driven out of business. And with the closure of the competitors, smaller publishers started closing as well because, with only a single portal now available to comic shops, their sales were falling off a cliff.

That 5,000-copy figure I quoted for Lorelei #1? That was the combined total from about ten distributors. My Diamond numbers were only in the hundreds.

In the end, Diamond ended up with every publisher because Marvel, you see, eventually came to realize that they sucked at self-distribution, shuttered Heroes World in 1997, and signed with the only game in town.

Of course, I’d stopped publishing before the Distribution Wars came to their bloody end, so I was just a spectator by that point. By the end of 1995, I’d decided that The ’Warp had to go on hiatus while I figured out what to do next.

But we weren’t out of the comics business just yet…

Pingback: SWC at 30: Enter: The Monster Hunter! | StarWarp Concepts